Story of a "broken mouth". This is the term that the author uses himself about it. The one who designated some serious wounded in the First World War. That day was one of the episodes of a new kind of war, led by fanatics, against a symbol of freedom of expression.

A bullet in the face

The Kouachi brothers burst into the small newsroom of Charlie Hebdo, strafing all over the place at close range with their Kalashnikov assault rifles. Drawing on everything that moves: Cabu, Wolinski, Charb, Bernard Maris, Tignous and others ... Including Philippe Lançon, who takes a ball in the face. Falling to the ground, in a pool of blood, next to the corpse of others, he sees the legs of one of the killers approaching him, expecting the coup de grace. "The brain of this man, this colleague, this friend, who was coming out of the skull a little". That of Bernard Maris. Exploded. Like the jaw of the author, who has not yet understood what was happening. Reading this extraordinary story, we saw (and dies) from the inside what until then was for us only vague descriptions, ready-made images of action movies summoned by our limited imagination, with their inevitable dose of clichés . A surface vision. Sandon makes the terrible effort to dive into and extract himself, more than two years later, beyond the precise film of what his eyes saw, what he actually lived, that is, felt. In this case, a kind of duplication, between the ego of his life before and the one who was beginning to understand ... "Bernard is dead, told me who I was, and I replied, yes he is dead, and we are united on him, on the point of exit of this brains that I would have liked to put back inside the skull and from which I could no longer detach myself ".

The author thought himself dead, his killers too. But this bullet in the face did not reach the brain. It's the bottom of his face that has been sprayed. A bullet in the jaw. He believed until then that "what had happened was a joke, while already guessing that it was not one, but without knowing what it was". He finally realizes, seeing on the screen of his mobile the reflection of the porridge that has become this face and that makes him "a monster". And telling himself, in a second state, that if he had gone a minute before, instead of changing his mind at the last moment to show Cabu the photos of a book on jazz, he would have met the murderers in the hallway. Who would then have riddled him with bullets, sending him where his companions - lying disarticulated around him - were holding hands for a long time.

An inquiry about himself

Follows an endless way of the cross, from emergencies to resuscitation, maxillofacial reconstruction operations at the hospital of Pitié-Salpêtrière to that of the Invalides, which a few meters from the tomb of Napoleon strives to maintain alive the victims of terrorism or wounded French armies in operation. Two years of a hospital journey punctuated by thirteen heavy operations, endless reeducations, back and forth between the block and the room, with pipes and vertigo, crucified by exhaustion, pain, doubt. For a long time without being able to speak, provided with a simple erasable Velleda tablet where he drew a few words. And love, finished? "On the shelf brought by the nurse I wrote hard, in capital letters:" It's fucking with Gabriela. "" Could his companion assume this? It was rough, but she could. Despite the worries she also had on her side, and the self-centeredness of which every injured person is obliged to show. "You have to prepare yourself psychologically because you're not good looking. This terrible and necessary sentence is told to her at the hospital by Florence, her sister-in-law, who, like her brother Arnaud, is very present during these long post-traumatic months at the hospital. Philippe Lançon is disfigured. Little by little, he starts writing again for Charlie Hebdo and Libération, a journalist investigating himself and chronicling his exit from the dead, his return to the living with a long pause in medical purgatory. Here, the pathos-free account of his life as a patient in the midst of white coats is a testament to an exceptional intelligence and humanity that concerns us all.

Women have a special role in it: Gabriela, but also her friends, who often know how to find the right gesture or word. And, above all, "her" surgeon of the Pity, named Chloe in these pages, sort of crossed the impossible with whom he maintains relations of almost love. All under the constant surveillance of the police Protection Service, and interspersed with official visits that give rise to striking portraits (including that of Francois Hollande flaming about the surgeon). Today, the author is repaired. With some sequels, but out of the tunnel: life has won. In closing this book, we say that literature too.

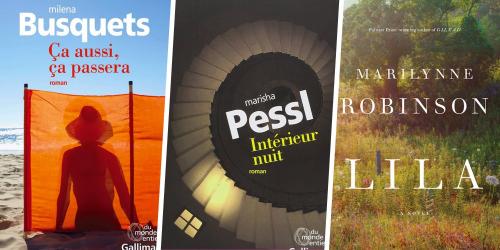

(*) The flap of Philippe Lançon, ed. Gallimard, 21 €.